Anatomy / Physiology of the human eye

Introduction

The human eye is divided into anterior and posterior segments, each of which serves a specific importance in the ophthalmic function. The human eye is situated in the orbit of the skull, which protects the eyeball, leaving uncovered only its anterior compartment. The eyeball itself is surrounded by 3 "layers". The outer and opaque "sclera", which is the white part of our eye, the middle layer - vital for nutrition - the "uvea" and the innermost layer, the "retina".

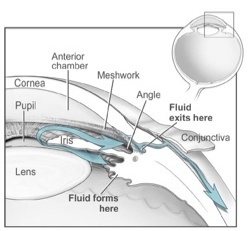

In the anterior segment of the eye (fig. 3), we initially find the cornea, which is the "windscreen" of the eye with significant refractive properties. Then we find the pigmented part of the eye - the iris – forming the pupil in the center. The pupil changes its size based on the source of light around it, allowing the light to gain access to the photosensitive posterior segment of the eye (fig.3).

|

|

The cornea with the iris form the anterior chamber of the eye filled with a special fluid, the aqueous humor. This fluid is important for the formation and nutrition of the anterior chamber and it is produced and drained out of the eye at respective rates. However, if the production is not followed by the respective drainage then the intraocular pressure increases beyond normal range, leading to glaucoma (fig.4).

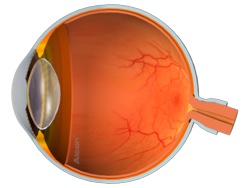

fig.5Behind the iris, we find the lens that due to its transparency determines the sharpness of our vision substantially. Decreasing its pupil and changing the shape of the lens, our eye can focus at close distances (through accommodation) just like an automatic photo camera. In older people, this ability is reduced and we need glasses for near vision (presbyopia). Getting even older, the transparency of the lens is reduced and it gradually blurs - causing cataract - significantly reducing our vision (fig.5).

fig.5Behind the iris, we find the lens that due to its transparency determines the sharpness of our vision substantially. Decreasing its pupil and changing the shape of the lens, our eye can focus at close distances (through accommodation) just like an automatic photo camera. In older people, this ability is reduced and we need glasses for near vision (presbyopia). Getting even older, the transparency of the lens is reduced and it gradually blurs - causing cataract - significantly reducing our vision (fig.5).

Behind the lens, we find the vitreous cavity of the eye that keeps its shape thanks to the gelly vitreous humor uniformly attached to the retina. This transparent and gelatinous mass under certain circumstances can either be detached from the retina (developing 'floaters' for the patient), or cause retinal holes which require urgent treatment.

|

|

|

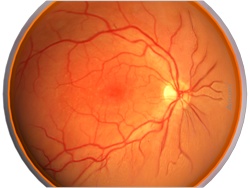

In the retina, there are microscopic photoreceptor cells, which are responsible for our day and night time vision. (fig.8). Finally, we can find our optic nerve - the 'wire' that transmits an image to the brain - and the macula, which is responsible for our central vision (fig 6.7).

fig.9Eye Movement

fig.9Eye Movement

Our eyes move in all directions with the help of six extraocular muscles, which define smooth movement of the eye by acting synergistically, and in pairs. A lack of coordination between the extraocular muscles leads to ocular deviations (strabismus).

Digital content is courtesy of Alcon Iberia

Digital content: Credit to National Eye Institute, National Institutes of Health.